The Parser is Dead; Long Live the Parser!

Bash++ v0.8 is arguably the most significant release yet apart from the project’s initial launch, at least in terms of internal changes. With this release comes a truly massive speed increase, thanks to the switch from ANTLR4 to GNU Bison to generate the parser.

Why the switch?

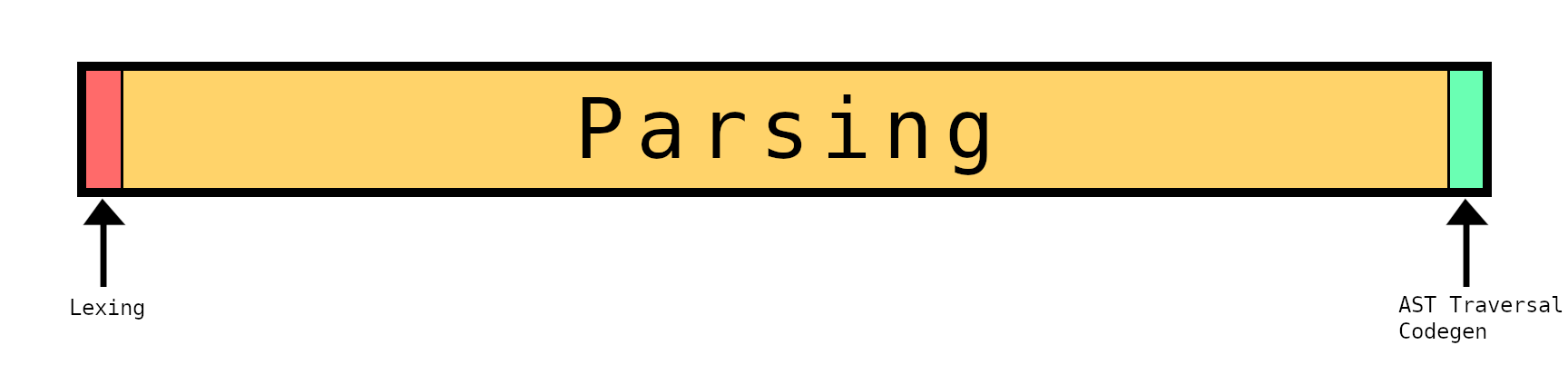

The kick in the teeth for me was when I benchmarked the compiler’s performance over each phase of compilation. I found that the graph looked something like this:

Parsing was taking up more than 99% of the total compilation time for larger programs.

ANTLR4 is a fantastic tool for generating parsers, and it served Bash++ well during its early development stages. However, as the project grew in complexity and size, the limitations of ANTLR4 became more apparent. Especially when compiling larger programs or when using the language server in an IDE.

I would absolutely recommend ANTLR4 for many projects – not only small ones. It just depends on your priorities and the purpose of your project. ANTLR4 is tuned for developer productivity and ease of use. It’s certainly a hell of a lot easier to use than Bison. It’s a great tool, its design decisions reflect its goals, and it’s the absolute top of the line for what it aims to do.

Bison, on the other hand, is designed for performance and efficiency. It’s a lower-level tool, it takes more effort to use (after reading the full 250-page manual, I still felt like I didn’t understand a damn thing about it), and it requires a bit more knowledge of parsing theory. But, boy is it fast. The biggest difference is the parsing algorithm – ANTLR4 uses an “adaptive LL(*)” algorithm, while Bison uses LALR(1).

Another feature I came to love about GNU Bison is that it yells at you until you fix your grammar. ANTLR4, ever the meek and dutiful servant, just silently makes due with whatever you’ve given it. Bison, a much more pig-headed kind of partner, won’t let up until you’ve satisfied its conditions, removed all ambiguities, and ensured that your grammar is LALR(1) compliant.

The switch

It was definitely a major undertaking. ANTLR4 did a lot of things for us automatically, like generating parse trees, which I had come to take for granted. With Bison, that all had to be implemented manually. But, the flip-side is that doing it manually gives us complete control over how things work, which is a powerful advantage. That control also allowed us to fix some long-standing bugs in the compiler (most notably in object reference handling) that were difficult to address with ANTLR4.

I’ve always tried to follow the principle: “parse as little Bash as possible.” In other words, the Bash++ parser should focus on Bash++ constructs, and let Bash do what Bash does. Unfortunately, this principle was originally carried through recklessly in the ANTLR4 implementation, leading to a parser that was ambiguous and slow. When writing an LALR(1) parser, it was obvious that “as little Bash as possible” was not quite as little as I had originally thought. Initially, for example, the Bash++ compiler didn’t even understand (or care to understand) the structure of a shell command.

This means that we were not able to simply “port” the old parser to Bison. Instead, we had to rethink and redesign the entire grammar from the ground up, which was a massive amount of work.

However, the end result is a parser that is not only significantly faster but also more robust and maintainable. The new Bison-based parser has dramatically improved the overall performance of the Bash++ compiler, making it much more responsive and efficient, especially for larger codebases.

Lexing

There’s another (somewhat subtle) difference between ANTLR4 and Bison. ANTLR4 runs the lexer in full before parsing begins – it lexes the entire source file into tokens, and only when that’s finished does it pass those tokens to the parser. Bison, on the other hand, interleaves lexing and parsing; the parser requests tokens from the lexer as needed during parsing.

The Bash language (and therefore also the Bash++ language) is extremely context-sensitive. The meaning of a token can change dramatically depending on where it appears in the source code. Take the following example:

case in in

in) in=in in in ;;

esac

How would you lex the token in? Well:

- The first time, it’s input to a

casestatement. - The second time, it’s the keyword

insignifying the end of the “case header” and the start of the pattern list. - The third time, it’s a pattern to match against.

- The fourth time, it’s a variable name.

- The fifth time, it’s a simple string to assign to that variable.

- The sixth time, it’s a command name.

- The seventh time, it’s an argument to that command.

Each occurrence of the word in has a completely different meaning depending on its context. This is just one of many examples of Bash’s context-sensitivity.

With ANTLR4’s approach of lexing the entire file upfront, it was difficult to handle these context-sensitive tokens correctly. It necessitated that the lexer should do some “parsing” of its own, which led to a massively complicated state-machine of a lexer that was difficult to maintain and reason about.

With Bison’s approach of interleaving lexing and parsing, we were able to simplify the lexer significantly. We can now get the parser to send signals to the lexer about the current context, allowing the lexer to make more informed decisions about how to tokenize the input without absorbing that complexity itself. Here’s an example from the parser of how it can now send a little help to the lexer:

bash_case_statement:

BASH_KEYWORD_CASE WS bash_case_header bash_case_body BASH_KEYWORD_ESAC { /* actions */ }

;

bash_case_header:

bash_case_input WS BASH_KEYWORD_IN BASH_CASE_BODY_BEGIN { /* actions */ }

;

bash_case_input:

valid_rvalue {

set_bash_case_input_received(true, yyscanner);

/* actions */

}

;

When the parser reduces (that is, recognizes) a bash_case_input, it calls the function set_bash_case_input_received(), which signals the lexer saying: “hey, we’re parsing a ‘case’ statement, and we’ve just seen the input expression. The next time you see the token in, treat it as the keyword in.” The lexer can then adjust its behavior accordingly.

We have to be a little careful with this approach, because the LALR(1) algorithm uses one token of lookahead. This means that the lexer may have already tokenized the next token by the time the parser “reduces” a given production.

In the above case, it’s fine, because the “lookahead” token after bash_case_input is whitespace, which doesn’t affect the meaning of in. But if, for example, the lookahead token was the in keyword itself, then the signal would arrive too late, and the lexer would have already mis-tokenized it – it would’ve decided what in means before receiving any signal. In such cases, we have to find other ways to disambiguate the grammar.

Building the parse tree

With ANTLR4, parse trees were generated automatically. With Bison, we have to build the parse tree manually during parsing. This gives us more control over the structure of the parse tree, allowing us to optimize it for our specific needs.

Here’s a great example of how this control allowed us to simplify the parse tree significantly. In Bash++, an object reference can take many different forms. For example, it can begin with an ordinary identifier, or it can begin with the keywords this or super. Not only that, it can be an lvalue reference or an rvalue reference (and we need to know at the time of parsing which one it is). Further still, it could be wrapped in a pointer dereference (preceded by the * operator) or in an address-of expression (preceded by the & operator).

Since ANTLR4 automatically generated nodes on the tree for each recognized grammar rule, that meant there were four different reference node types in the parse tree:

- Lvalue object references (external)

- Rvalue object references (external)

- Lvalue self-references (

this/super, internal) - Rvalue self-references (

this/super, internal)

And further, that those nodes were themselves child nodes of yet another node representing the pointer dereference or address-of expression, if applicable.

Obviously, this was very hard to deal with.

With Bison, we were able to simplify this significantly. We created a single parse tree node type for object references, and we added fields to that node to indicate whether it’s an lvalue or rvalue reference, whether it’s a self-reference or external reference, and whether it’s wrapped in a pointer dereference or address-of expression. It’s much simpler to only have to deal with a single node type for object references, rather than four different types.

The results

The results speak for themselves. The new Bison-based parser is many orders of magnitude faster than the old ANTLR4-based parser. Here’s a benchmark comparing the two parsers on a random sample of approximately 60,000 lines of Bash++ code:

| Parser | Time Taken |

|---|---|

| ANTLR4 | 9 minutes 11 seconds |

| Bison | 0.65 seconds |

That’s a speedup of over 800x!

Of course, given the nature of the Bash++ language, it’s unlikely that very many Bash++ programs will be 60,000 lines long. However, the speedup is still very significant even for smaller programs. The Bash++ test suite for example is approximately 3,000 lines of code, and the parsing time for that has dropped from around 30 seconds to just a fraction of a second.

So long, ANTLR. You served us well, and we’ll always remember you!

The parser is dead; long live the parser!